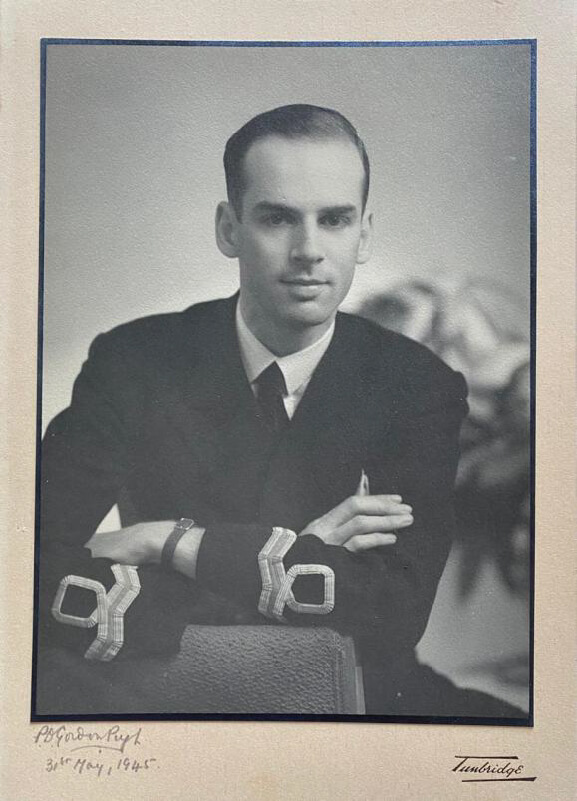

He is something of a mystery, with not much known about him. What we do know goes something like this. Patterson David Gordon Pugh, OBE, FRCS (he earned his medal and professional status because of study and distinguished naval service) was born in 1920 to the son of a doctor in Carshalton, Surrey. He went to Lancing College and then to Jesus College, Cambridge University (impeccable alma mater institutions) and graduated as a doctor after working at the Middlesex Hospital in London.

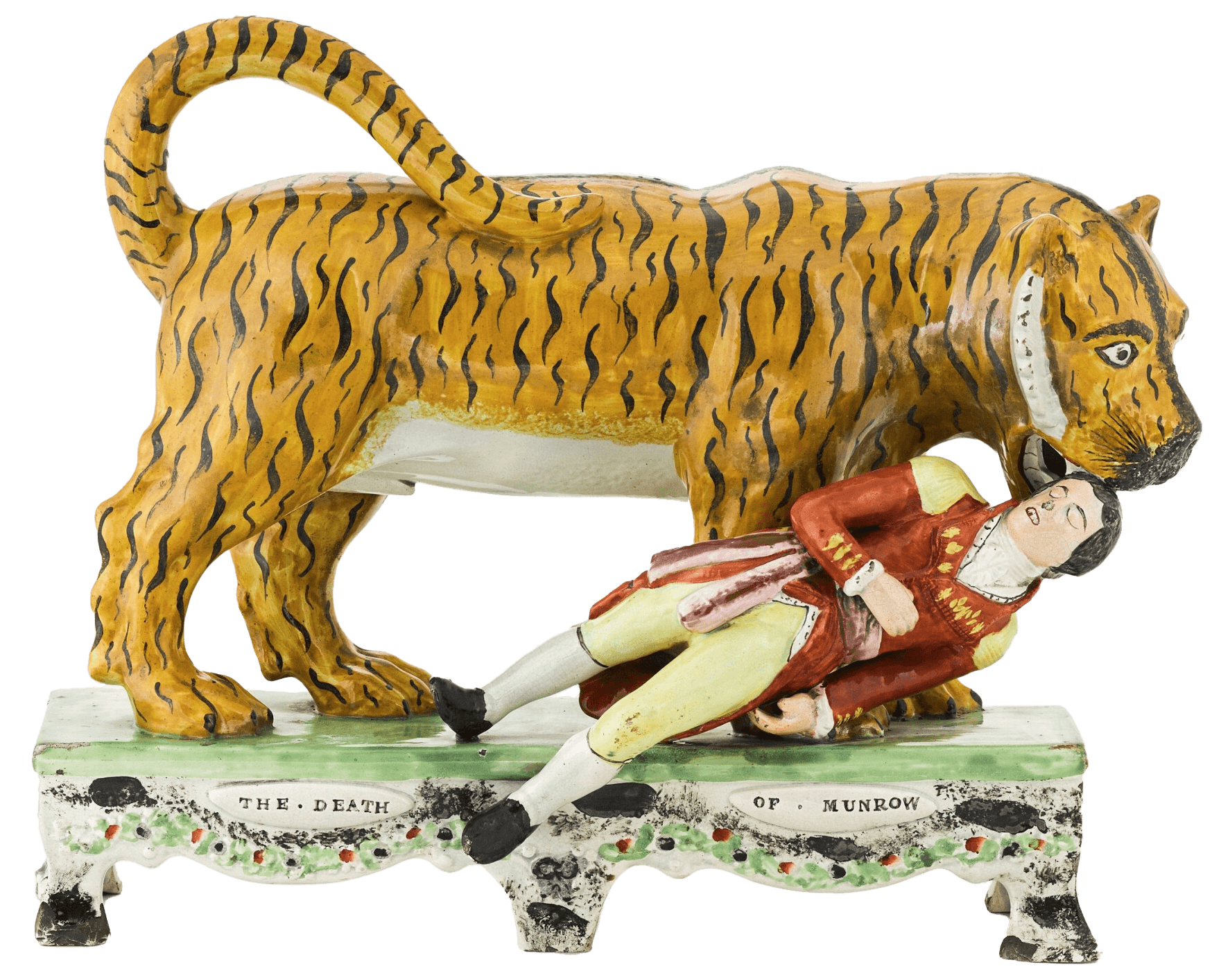

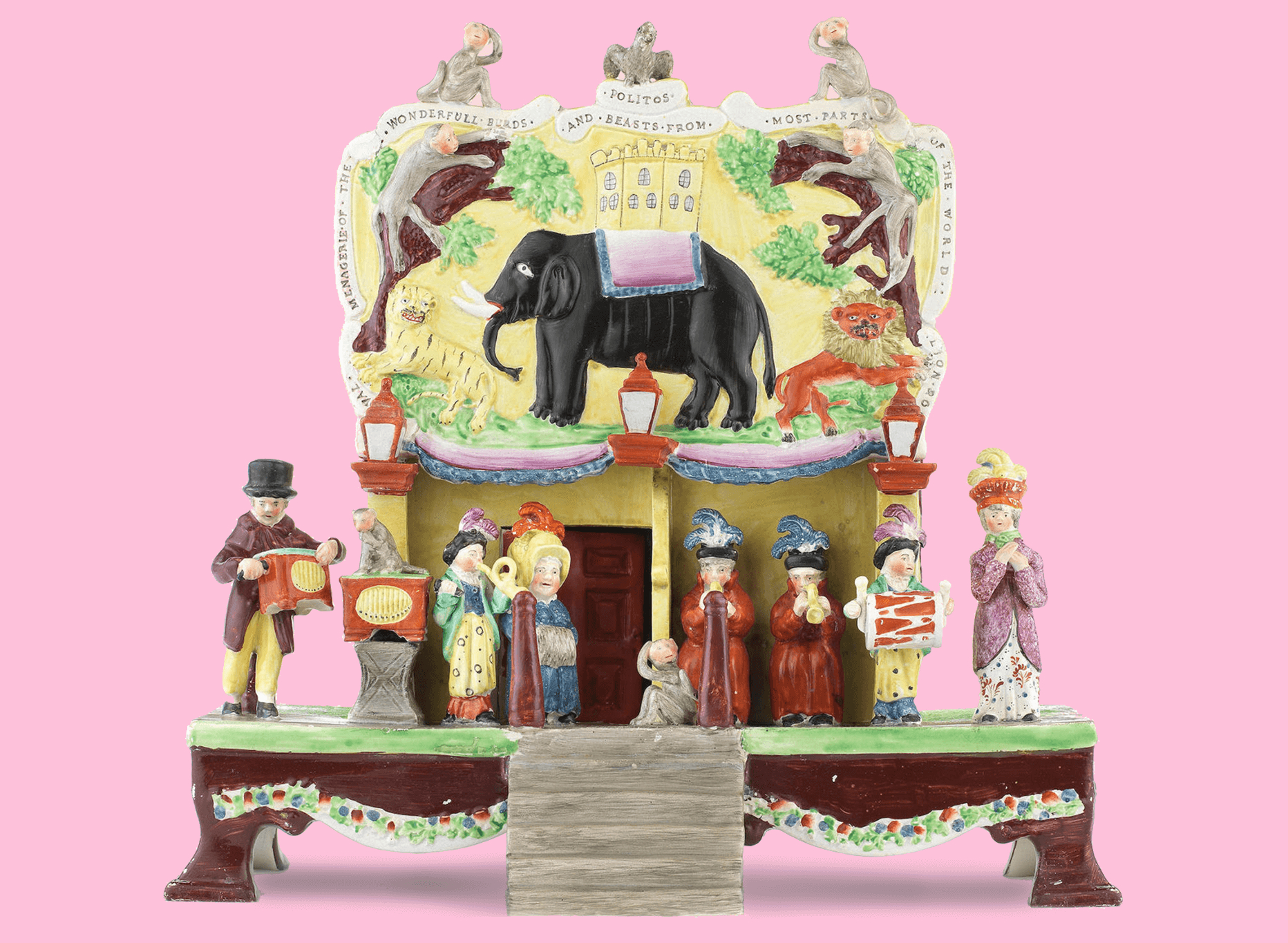

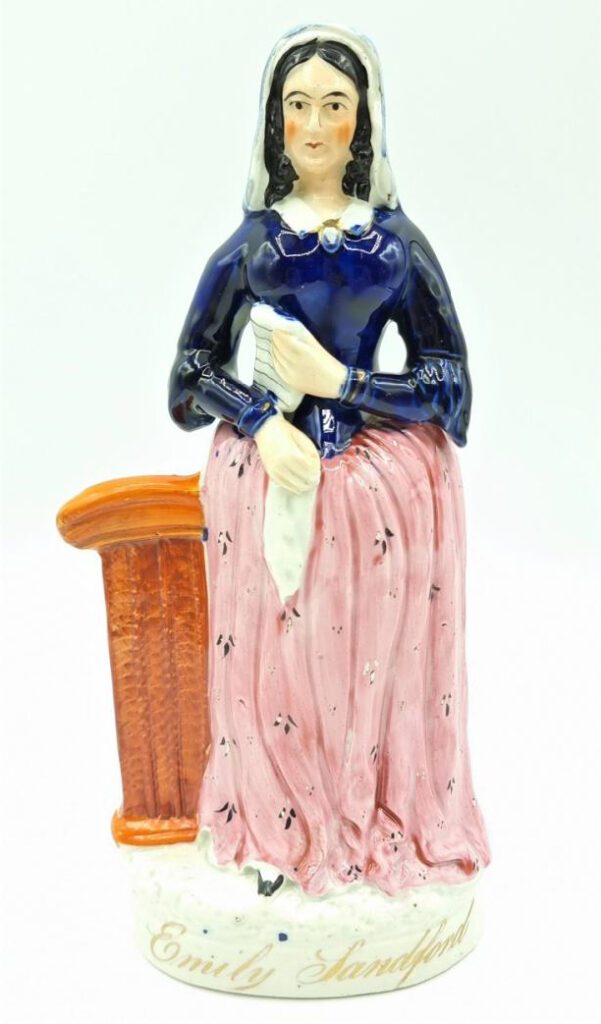

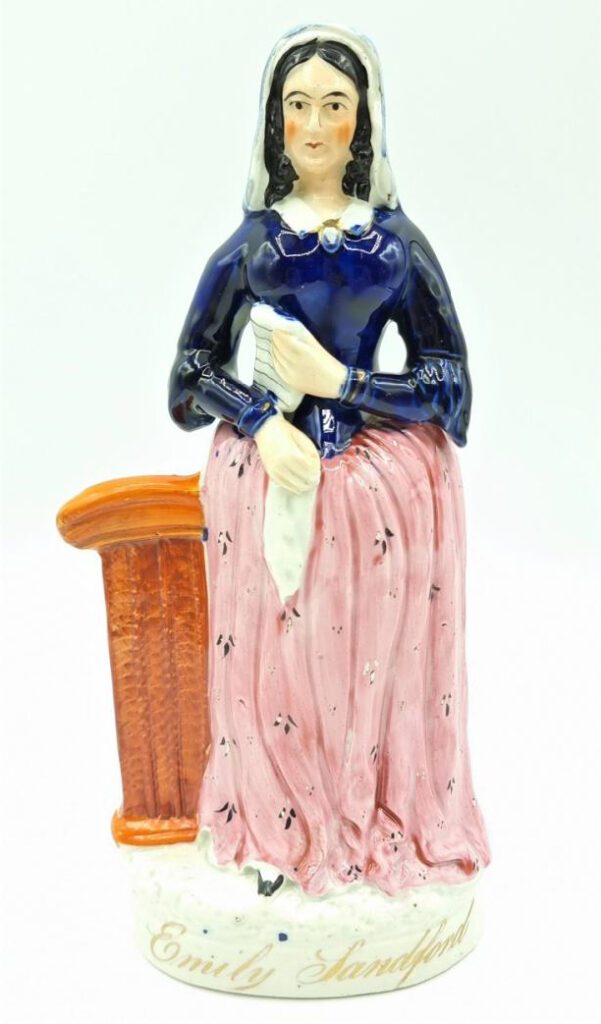

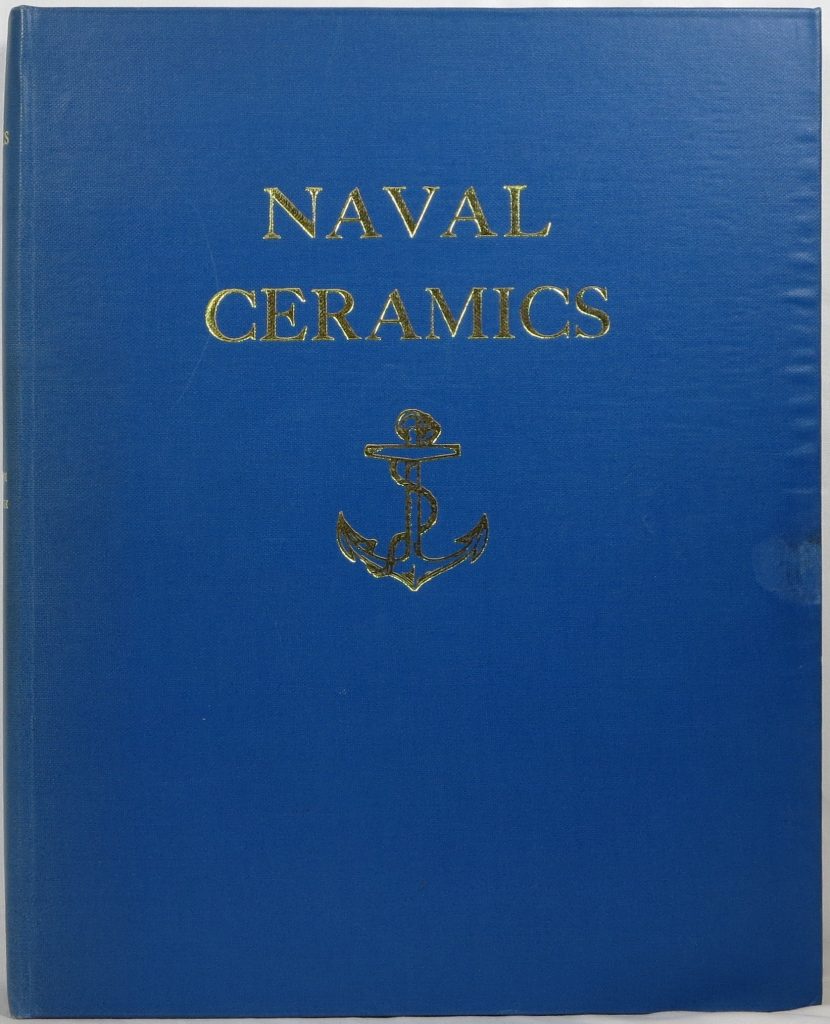

As an orthopaedic surgeon he joined the Royal Navy, working his way up the officer ranks to become a Surgeon Rear-Admiral in 1975 and an Honorary Surgeon to the Queen. He became a serious collector of figures in the 1960s and 1970s, writing about his researches in published books, starting with Nelson and his Surgeons (1968) and going on with Naval Ceramics (1971) and Heraldic China Mementos of the First World War (1972). He later said that his first Staffordshire figure acquisition was Robert Burns because of the brilliant blue of the poet’s coat. Next came ‘The Death of Nelson’ and Florence Nightingale and from then on he was hooked. (Not an unusual occurrence for Staffordshire figure collectors). As a naval officer, it’s not surprising that he specialised in collecting naval figures – a unique group which has no parallel.

In 1972, Surgeon Admiral Pugh made an offer to the City Museum in Stoke-on-Trent. He was moving house (or ship) from his posting in Plymouth and felt he had to find a new home for his substantial collection. After his offer was gratefully accepted, he loaned over 400 figures to the museum for a period of six years. In 1973 a display of the collection, opened to the public, attracted nearly 6,000 visitors.

In 1980 Pugh with his wife Margery decided to retire to Cape Town in South Africa to continue his research and write about Staffordshire figures. He said he had decided ‘with much regret’ that the Stoke collection would have to be sold and thus dispersed. Reluctant to lose its treasures, the museum opened up an appeal fund. Over £50,000 was raised and deftly trousered by the Surgeon-Admiral who probably celebrated his sale with a couple of bottles of South African chardonnay.

The collection remains in the museum where it is stored and occasionally displayed to the public as the Pugh Collection. A 12 page printed catalogue was prepared and published as Staffordshire portrait figures : a catalogue of the P.D. Gordon Pugh collection in the City Museum & Art Gallery in 1988 (text available here; no digital illustrated version exists).

Pugh’s figures are not digitised so cannot be viewed online but the museum catalogue does list many other Staffordshire naval figures – over a dozen Nelsons, Sir John Franklin and Lady Franklin and other explorers, and several anonymous sailor figures – sailors with their mothers, sailors with girls, sailors energetically dancing (it was part of popular Victorian mythology that sailors danced hornpipes twenty-four hours every day).

Gordon Pugh died in South Africa in 1993 but his fame (to discerning and sensible people) lives on. His son, Lewis Pugh, is an endurance swimmer who among other feats swam across the North Pole and the full length of the river Thames and is a campaigner in the global warming crusade. Lewis tells the story of how the Pughs behaved at public auctions. When Gordon Pugh arrived – well-known and a keen bidder – prices went up. So they devised a tactic. Gordon sat in the front row, silent, impassive, his hands at rest. Margery, unknown and in the back row, made the bids to secure another Staffordshire figure. And so their collection grew.

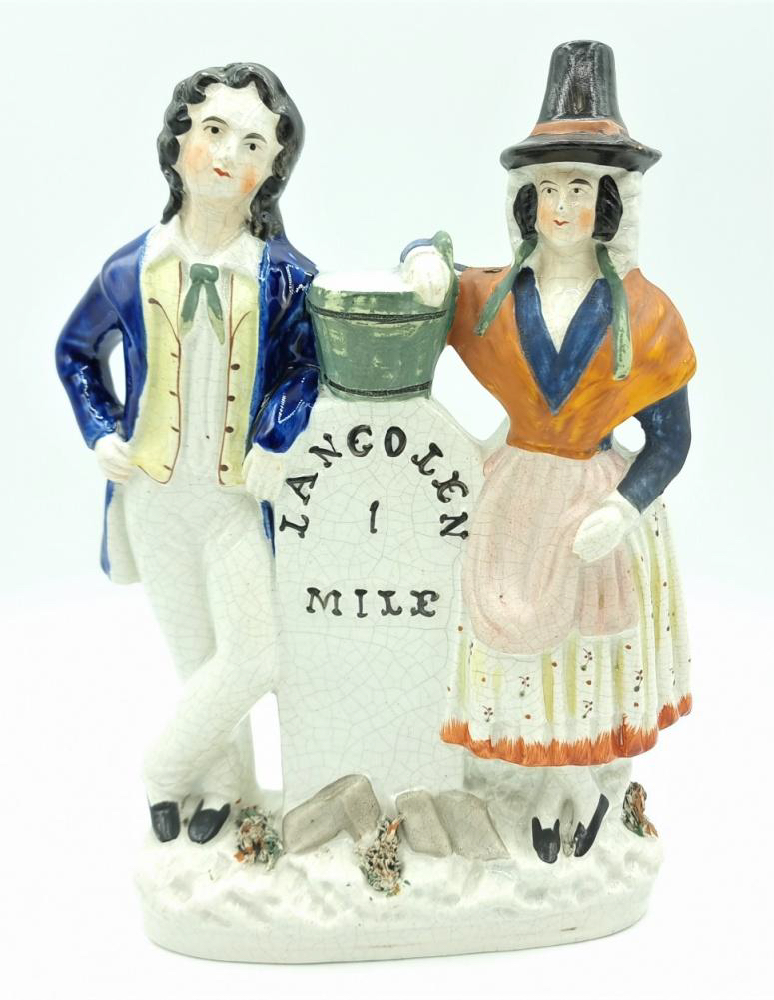

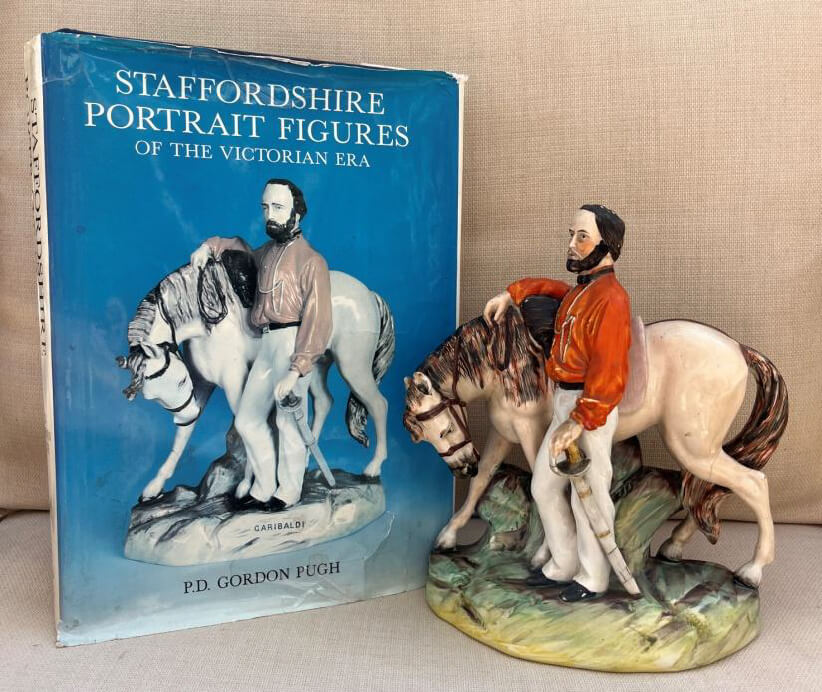

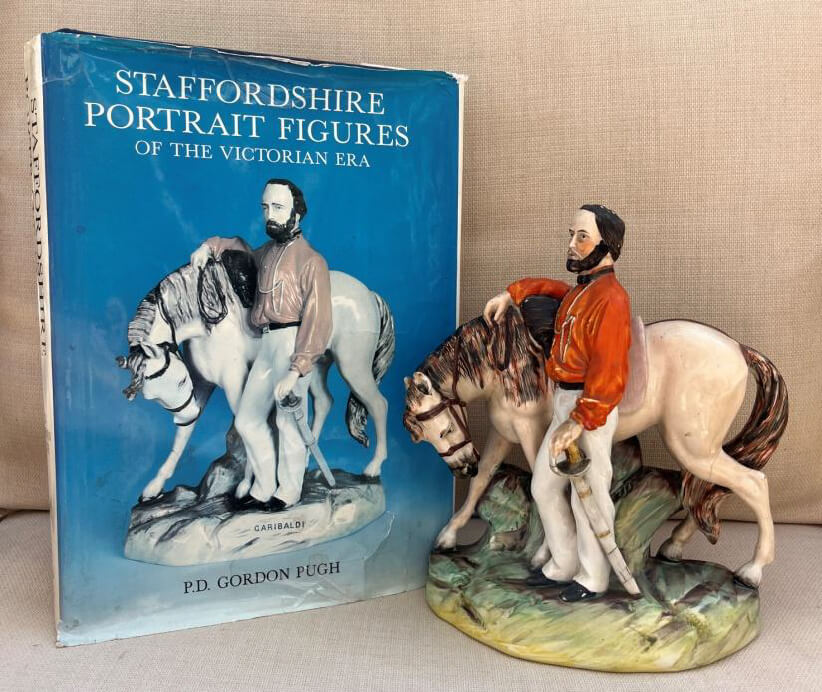

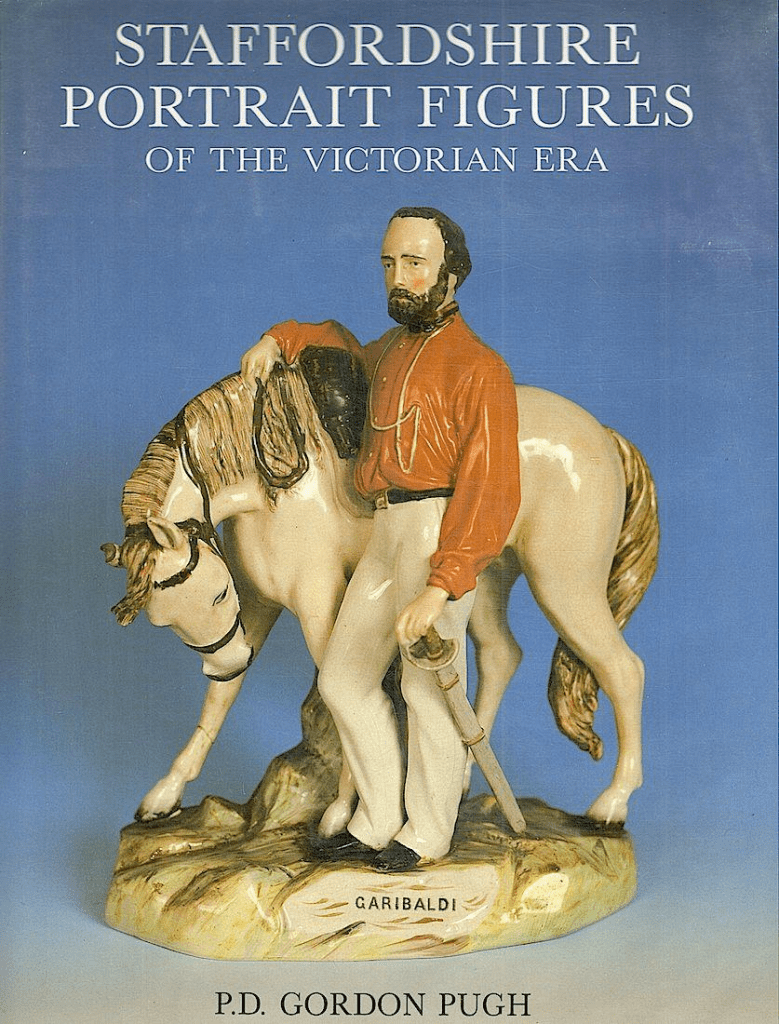

Gordon Pugh’s great achievement is for Staffordshire figure collectors the publication of the Staffordshire Portrait Figures of the Victorian Era, a vast compendium of information and illustrations of over 1500 portrait figures of the 19th century, displaying his attention to detail in careful reference numbering. He said that he and Margery had travelled many thousands of miles throughout the UK and in Europe to photograph and log figures in people’s collections. The work was a joint venture with his wife. Margery took the pictures and typed the manuscript.

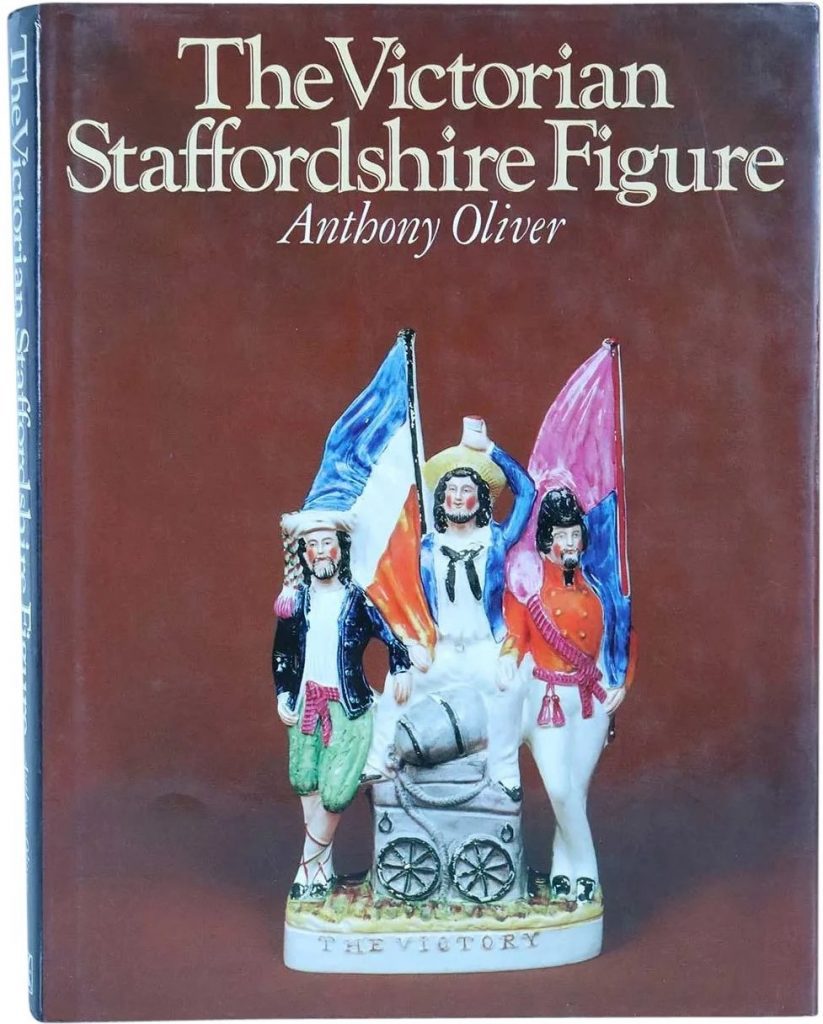

Their work of art, which took seven years to research and write, was first published in 1970 when he was a serving Royal Navy officer; it was a triumphant success after years of collecting and writing. Alongside his book and at much the same time (in 1971), Anthony Oliver published his more modest guidebook for beginner collectors, The Victorian Staffordshire Figure. Pugh’s mighty volume in a revised edition appeared in 1981, with another in 1987 containing an increased number of coloured illustrations.

The 1987 edition was published by the Antique Collectors Club and copies can be bought online or in antique shops that offer old books for sale. (This is where I found my copy, seized and bought with relish).

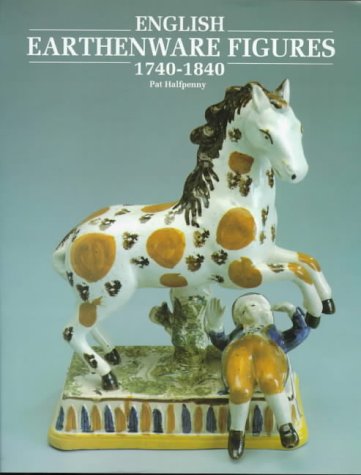

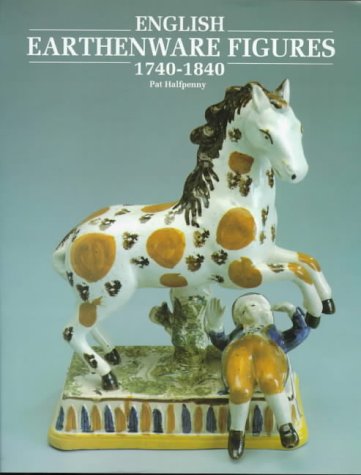

Finding a picture of Gordon Pugh was difficult but his son, Lewis Pugh, came to the rescue with a portrait of a youthful naval officer taken around 1945 and is included in this article. The Stoke Museum has his Staffordshire figures but not his portrait in any form – until now. The museum does have two documents of great interest in the Pugh story: the 1989 catalogue of the Pugh Collection mentioned above and a display catalogue of an exhibition held in the 1980s, English Earthenware Figures 1740-1940.

The museum has not yet digitised the Pugh figures so a visit to see them in person is necessary, camera in hand. They are not on display but an appointment can be made to view them, time and staff permitting, by contacting the museum well in advance.

Pugh reading list

(1987 edition); P.D. Gordon Pugh, Margery Pugh

(1991 reprint); Pat Halfpenny

Anthony Oliver

Margery Pugh, P.D. Gordon Pugh

Alan Jamieson has a modest collection of Staffordshire figures, none of which are from the Pugh hoard.

An earlier version of this article appeared in the Spring 2023 Staffordshire Figure Association members’ newsletter.