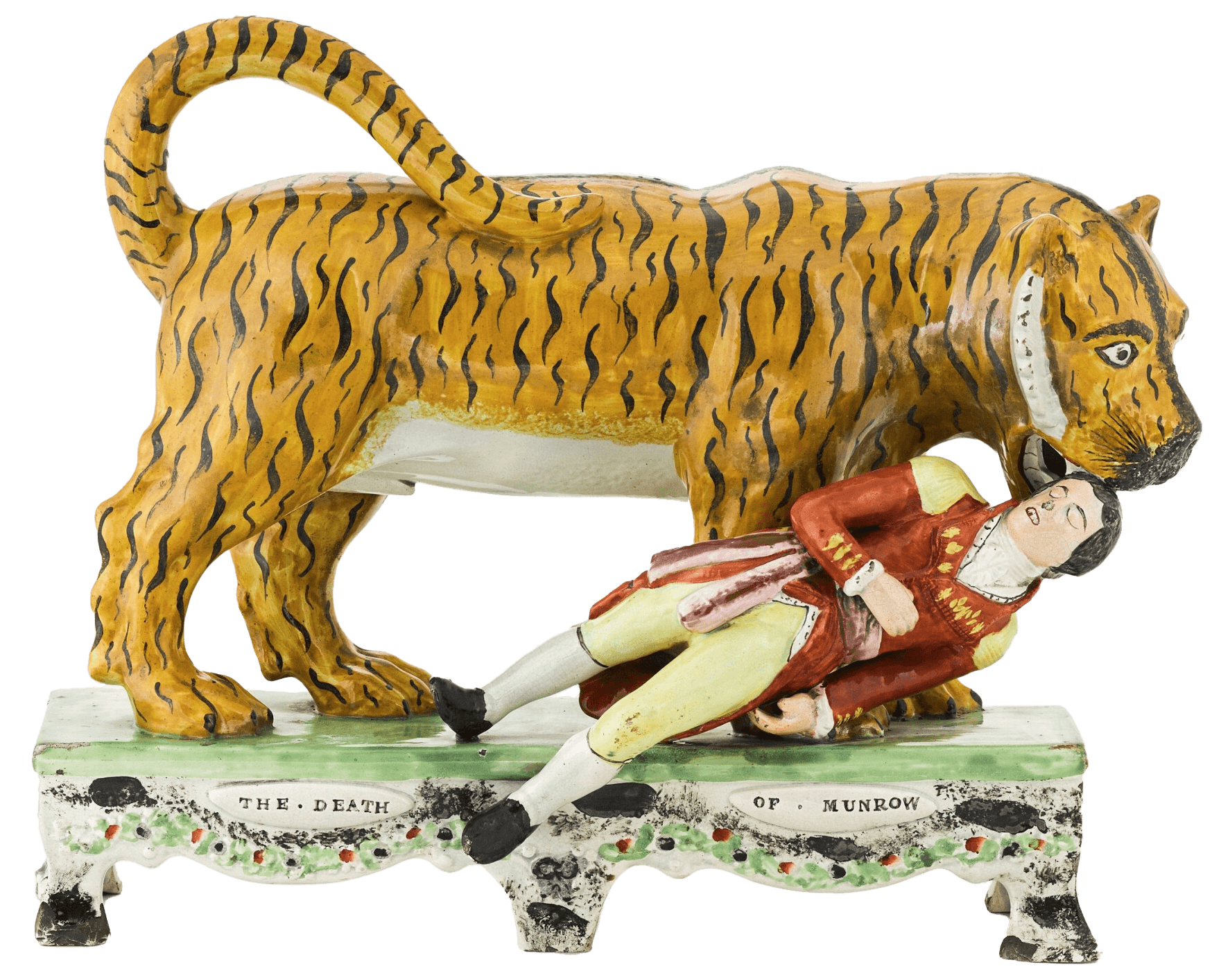

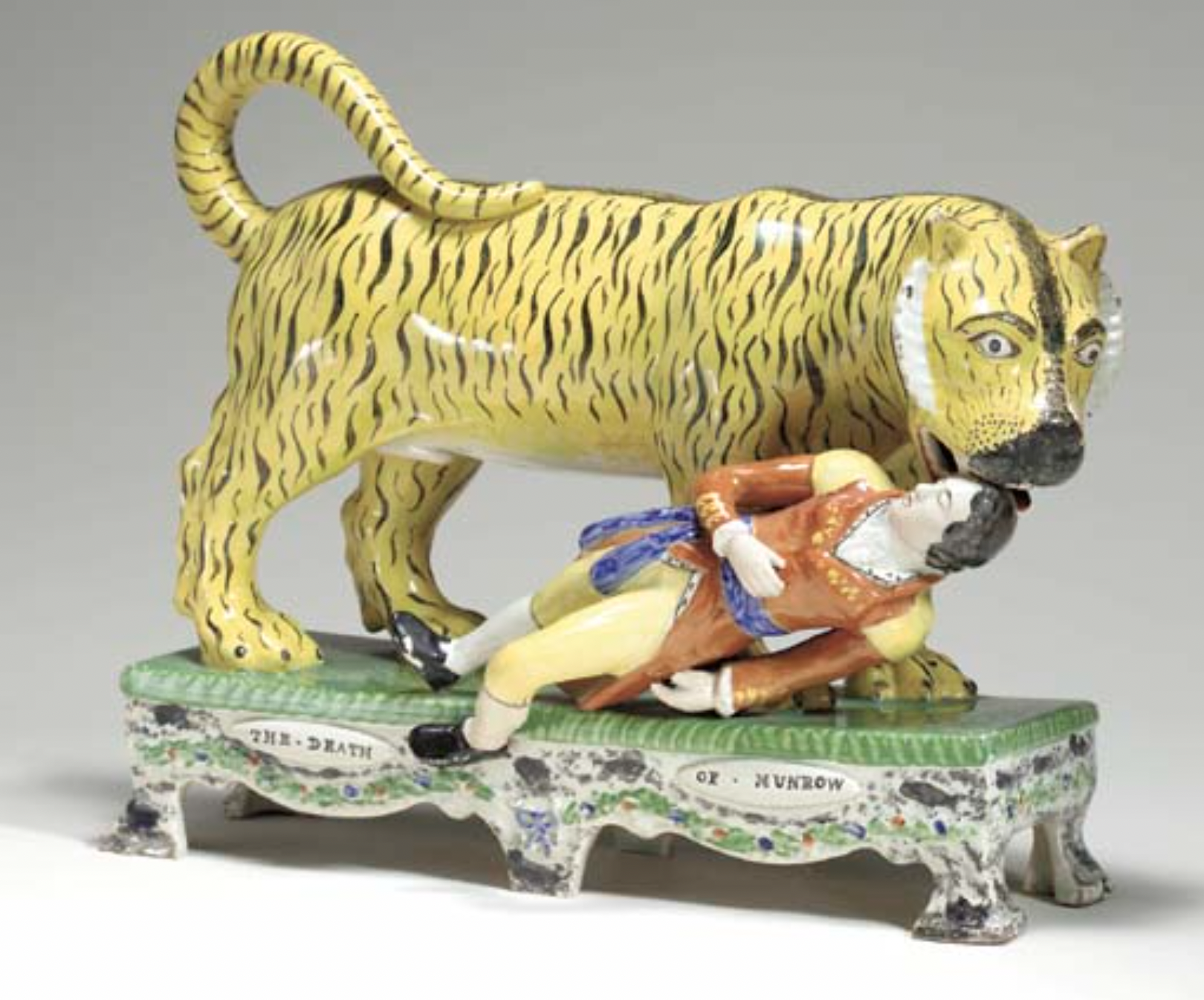

As it happened, young Hector Munro was the tiger’s teatime treat. Attending a tiger hunt in Bengal in 1792 and perhaps distracted by the call for tiffin, he was attacked and had his face bitten off by a ferocious assailant. The reason why this gory episode is drawn to your attention is because of a sale at Sotheby’s in November 2023 when the ‘The Death of Munrow’, a rare figure possibly from the pottery of Obadiah Sherratt in Burslem between 1825 and 1830, came up for sale. And was sold too, for an eye-watering hammer price of £30,480 plus tax and commission.

The Munro story goes something like this (courtesy of the Sotheby sales catalogue, entries in Staffordshire figure catalogues and British Army records). Hector Munro was the illegitimate son of another Hector, Sir Hector Munro, the 8th Laird of Novar, the Member of Parliament for Inverness and an army general with a distinguished fighting career in India. The younger Hector (who is mistakenly called Hugh in some accounts) joined the East India Company as a cadet and when only sixteen he accompanied a picnic expedition in Bengal on 22 December 1792. Sangor Island, near Calcutta, was popular with game-hunters but was dangerously crowded with peckish tigers.

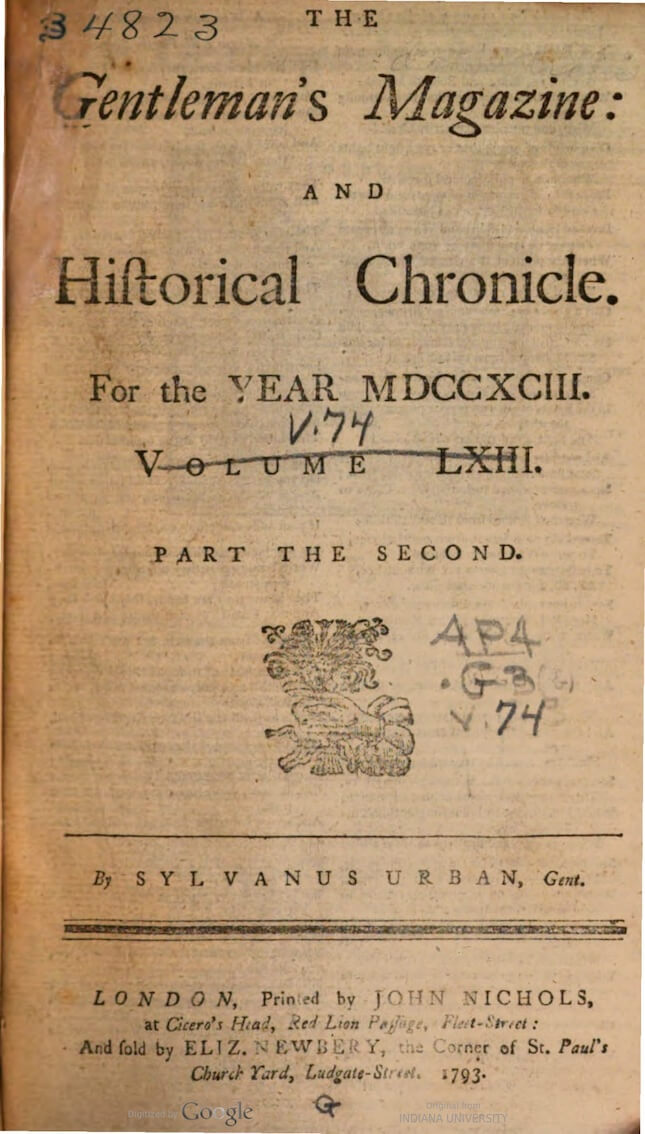

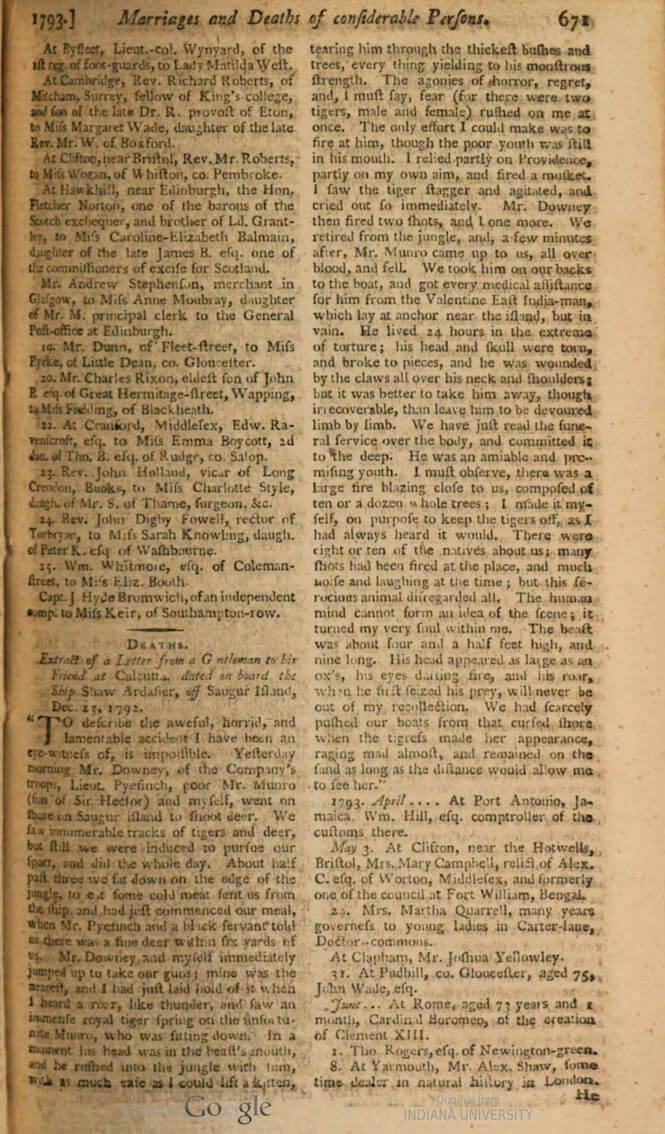

Munro and his companions lit a fire and sat beside it, possibly sipping a pre-lunch beverage. You might say he took his eye off the ball (or the tiger) for he strayed into the undergrowth, and was caught, mauled and died the next day. In an edition of The Gentleman’s Magazine of July 1793 there was an account of ‘the awful, horrid and lamentable accident’. Another Munro, his brother Alexander, also suffered a tragic death, consumed in 1804 by a shark off Bombay. We are tempted to reflect that the Munro clan lived exciting lives although they did regularly exhibit their unfortunate habit of failing to spot the approaches of marauding fauna.

To continue the Hector Munro (or Munrow or Monroe, take your pick) story. The magazine of July 1793 pulled no punches: ‘I heard a roar, like thunder and saw an immense royal tiger spring on the unfortunate Munro … In a moment his head was in the beast’s mouth and he rushed into the jungle with him, with as much ease as I could lift a kitten’. The pre-Victorian and later audiences enjoyed their gory tragedies and the tale was told in other publications and acted out in the theatre. Thus it became an object that tempted Staffordshire potters and led to a modest output of figures.

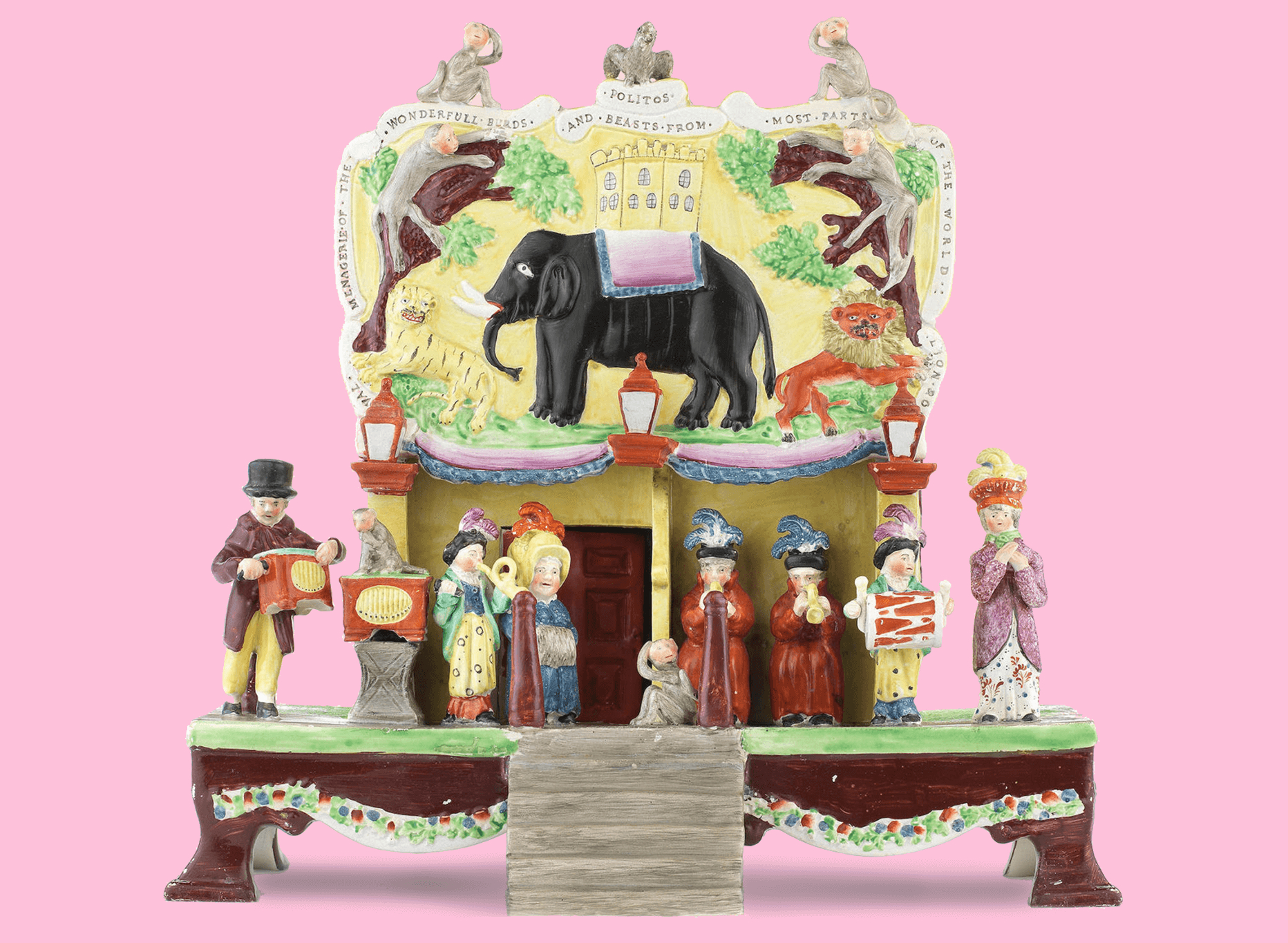

Sometime after Hector’s demise a lifesize mechanical pipe organ was made for Tipu Sultan of Mysore, who derived particular pleasure from the young man’s misfortune. It was seized by the British following the Sultan’s death at the Battle of Seringapatum in 1799, and transported to London. The machine which piped noises that imitated the roaring of a lion and the anguished cries of its victim was first exhibited at East India House in the City of London in 1808 where it was much admired and marvelled at. This publicity inspired the potters to produce the Munro group thirty years after the sad incident.

The Indian Museum, as East India House became known, moved several times before parts of the collection, including Tipu’s tiger, were transferred to the South Kensington Museum, later renamed the Victoria and Albert Museum, where it remains today, a much-admired exhibit – especially by younger visitors.

Back to our Staffordshire ‘Death of Munrow’ group and the hammer price of over £30,000 (with tax and commission the total will top £36,000), which seems astounding. However, according to Sotheby’s, it is original, around 1825, and a rare figure, so justifying its price (or so Sotheby’s say, other people might have a different opinion). Few figures were produced at this time and even fewer have survived for 200 years. Many would have been destroyed because of failures in the kiln and others will have been later lost, damaged and thrown on a rubbish heap. Perhaps then this justifies £30,000 plus, which is remarkably not the highest price realised for one of these gruesome figures.

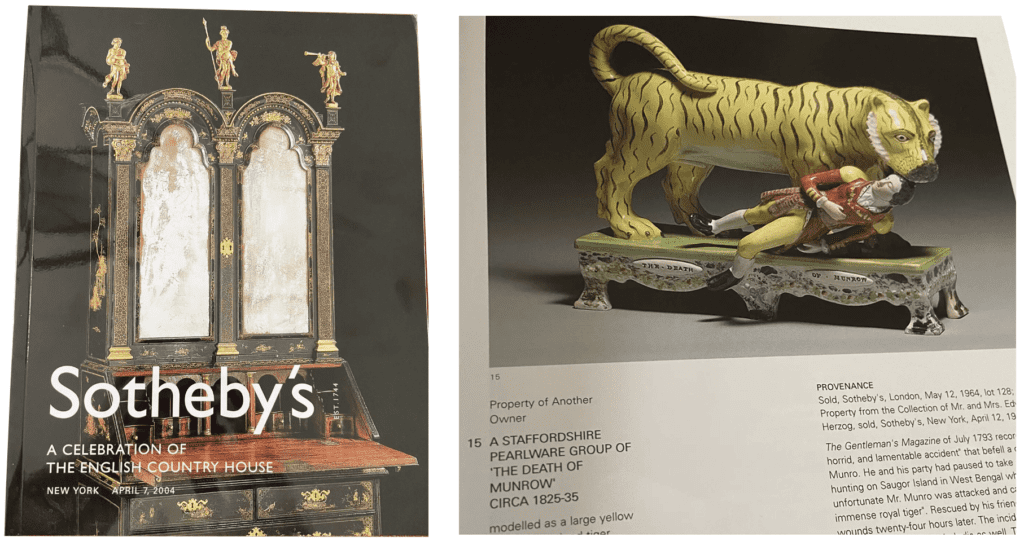

This accolade goes to a ‘Death of Munrow’ sold by Sotheby’s New York on 7 April 2004, for $130,000 (at the time, equivalent to £74,285) plus buyer’s premium. In the accompanying Sotheby’s A celebration of the English Country House sale catalogue the figure was estimated at $25,000-$35,000 and was recorded as having ‘some minor restoration’.

Looking for other illustrations, there is a ‘Death of Hector Munroe’ in Anthony Oliver’s book, The Tribal Art of England. ‘The horrid story’, wrote Oliver, ‘replete with gory details, made a deep impression on the public at the time’ and ‘would surely have satisfied the most bloodthirsty of his customers’.

Another illustration is in A Potted History: Henry Willett’s Ceramic Chronicle of Britain catalogue courtesy of the Brighton and Hove Museum. Stella Beddoe, the author and editor, tells the story of poor Hector (although she calls him Hugh) alongside a fine illustration of the tiger and its luncheon. This version of the enamelled pearlware Munro figure, dressed in the uniform of an ensign is on show as part of the Willetts Collection (in 2024 the Willetts Collection is being held at the V&A whilst the Brighton and Hove Museum undergoes renovation) and another fine figure is in a showcase in the V&A as part of its own collection.

More Deaths Gallery

If the Sotheby’s auction prices seem a trifle on the high side, there are bargains to be had. As we write this article an offer of a ‘Death of Munrow’ figure was on eBay. As they say, the price was right, at a final price of £56 after brisk online bidding. There could, however, be a snag. At this modest price, blood-stained Hector and his fierce attacker has to be a reproduction, a fake, a dud. In the 1970s boatloads of fakes were shipped from Shanghai and other eastern manufactories to sell to gullible western buyers. Hector was probably sold for £3, and so £56 on eBay seems a good purchase – for a reproduction or dud. An unworthy thought does come into one’s mind: the £30,000 plus Tyger couldn’t possibly be a dud, could it? Surely not. The seller, the dealer, the Sotheby researcher, the buyer – or all of them – couldn’t possibly be wrong, could they? No, of course not (says the buyer!)

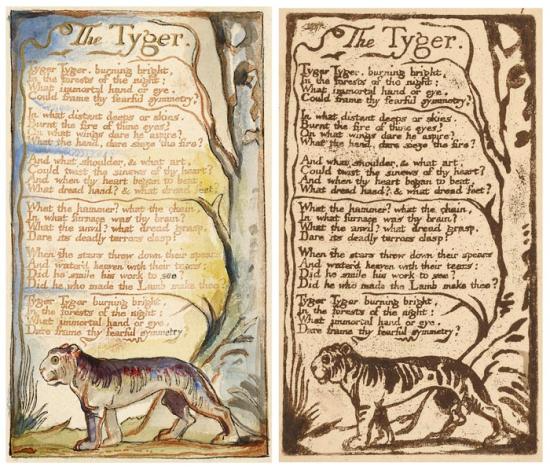

Perhaps we might finish with lines from William Blake’s famous poem of 1794 – published less than two years after Munro’s death. Some scholars speculate that the firsthand witness’s description of the tiger and its ‘eyes darting fire’ inspired Blake’s analogy:

‘Tyger, Tyger, burning bright

In the forests of the night

What immortal hand or eye

Could frame thy fearful symmetry’.

William Blake: The Tyger

Plates from two copies of Songs of Innocence and of Experience, Copy K, ca. 1795, Purchased by Pierpont Morgan with the Toovey collection, 1899

Alan Jamieson has a modest collection of Staffordshire figures, but so far no ‘Death of Munrow’. An earlier version of this article appeared in the Winter 2024 Staffordshire Figure Association members’ newsletter. Additional research by Sarah Gillett.

Further reading on the ‘Death of Munrow’:

Amusing and interesting article by Colin Munro in the London Review of Books:

https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v40/n01/colin-munro/thus-were-the-british-defeated