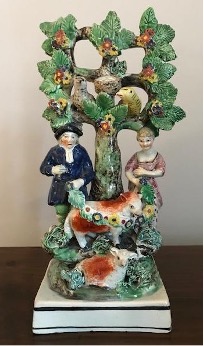

Probably no other Staffordshire pottery figure was produced in more forms and sizes than the beloved sheep. If you go to Myrna Schkolne’s series of books titled Staffordshire Figures, 1780-1840, especially Volume 3, you will be astonished by the vast number of sheep figures, and almost certainly there are others out there that are not yet illustrated.

If you include Prattware figures, Victorian sheep figures, as well as those made in Wales and Scotland, the numbers of potted sheep figures escalate even further. Add in those figures which include sheep in their decor, such as many in the musicians grouping do, you then get a sense of how important and revered sheep were as part of the British economy and social structure. Sheep have been farmed in the UK since Roman times and have been a traditional and important part of the history of British society by providing meat, milk, and wool for the population.

Historically, wool was big business in medieval England. There was enormous demand for wool, mainly to produce cloth and everyone who had even a little land raised sheep. The English did make cloth for their own use, but very little of the cloth that was produced was sold abroad. It was the raw wool from English sheep that was required to feed foreign looms. At that time the best weavers were in Flanders and in the rich cloth-making towns of Bruges, Ghent and Ypres, and they were ready to pay top prices for English wool.

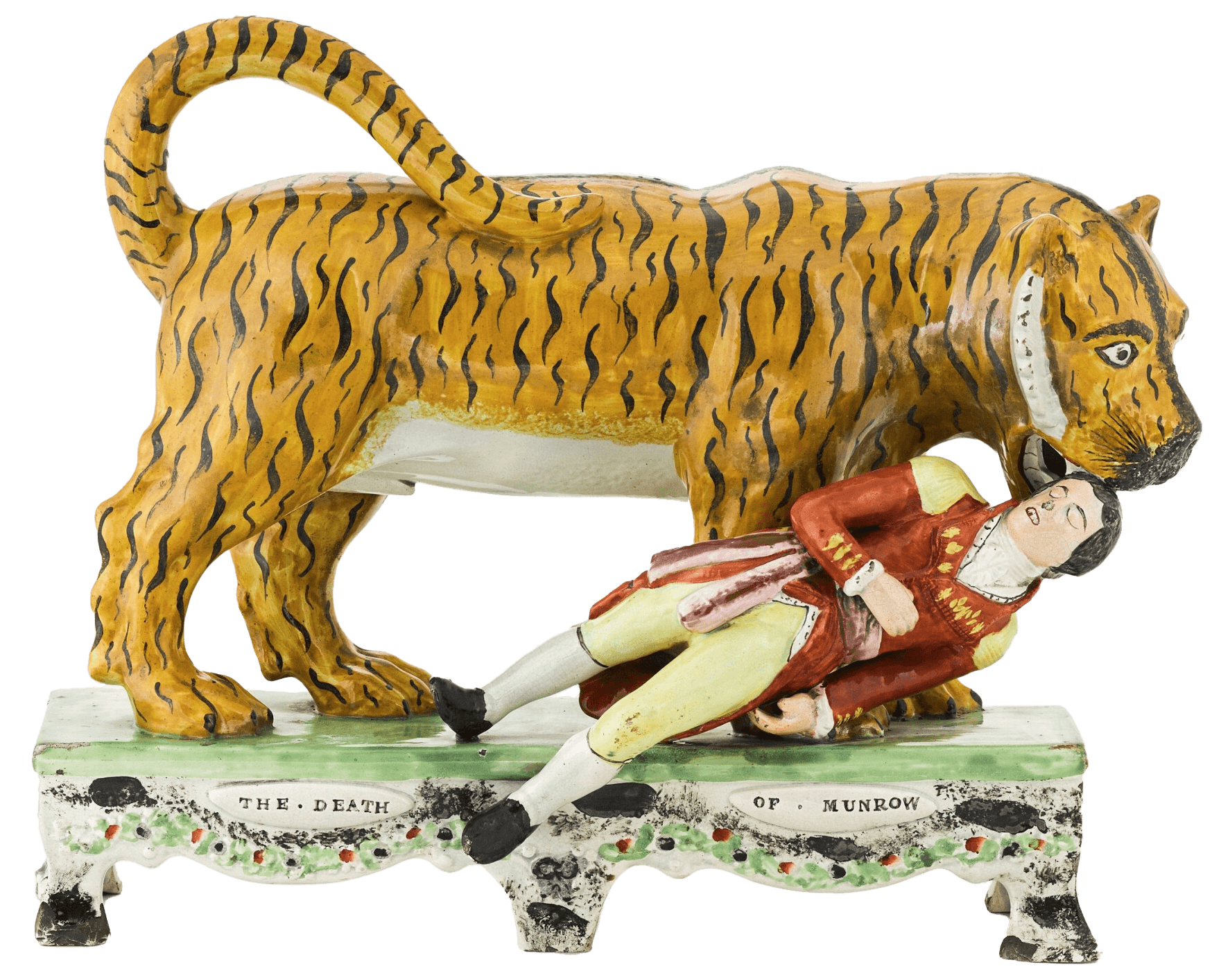

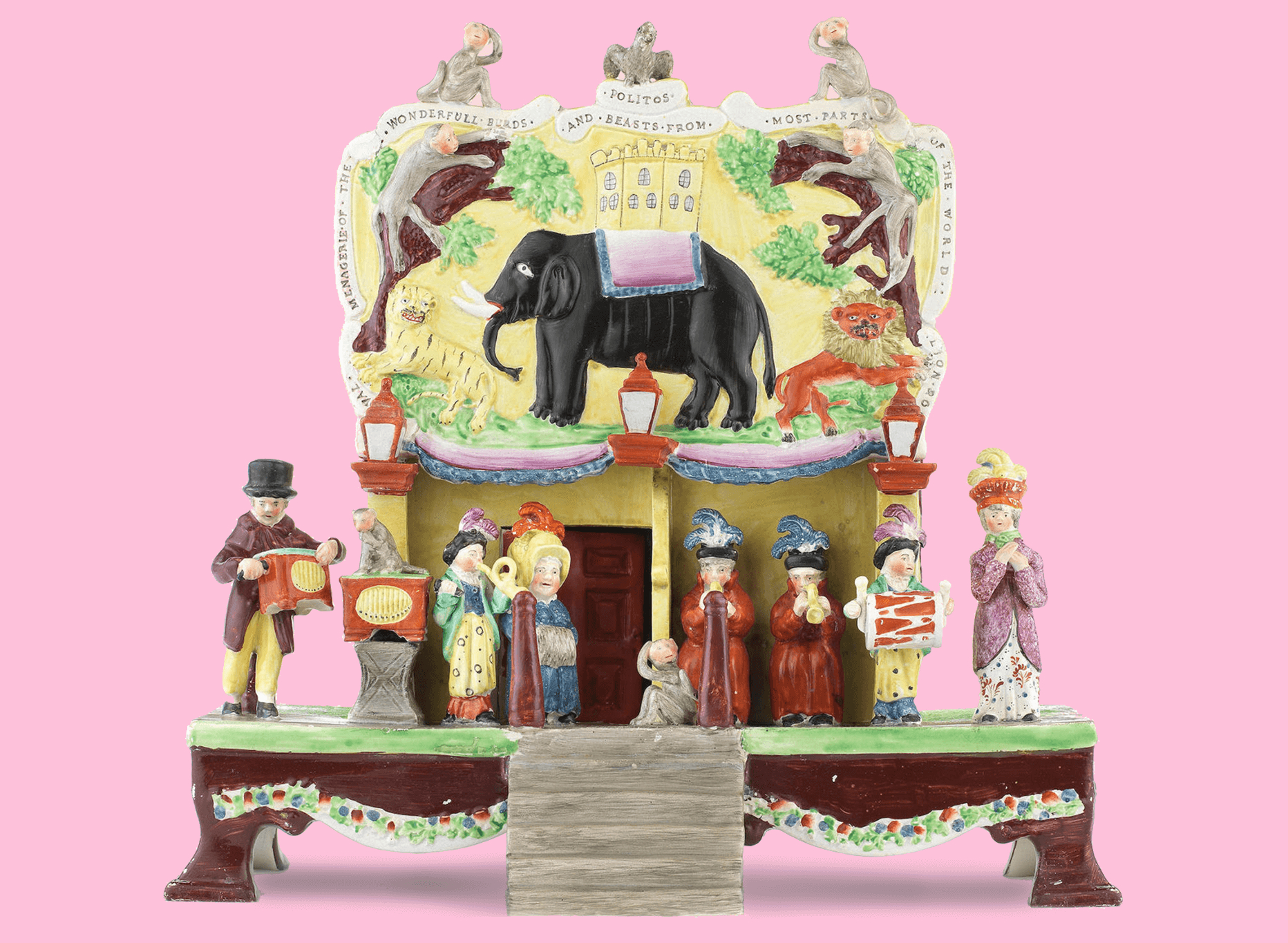

Win Hook Collection

Wool became the backbone and driving force of the medieval English economy. As the wool trade increased, the great landowners began to count their wealth in terms of sheep. A tax was levied on every sack of wool that was exported which provided a regular revenue source for the monarch.

The wool success story continued right into the Victorian period when Leeds was at the forefront of a cloth-making industrial revolution. Leeds economy, it is said, was built on wool. All the sheep in England were not enough to meet the demand, so wool was shipped in from as far away as Australia and New Zealand for the mechanised Leeds mills, the largest in the world at that time.

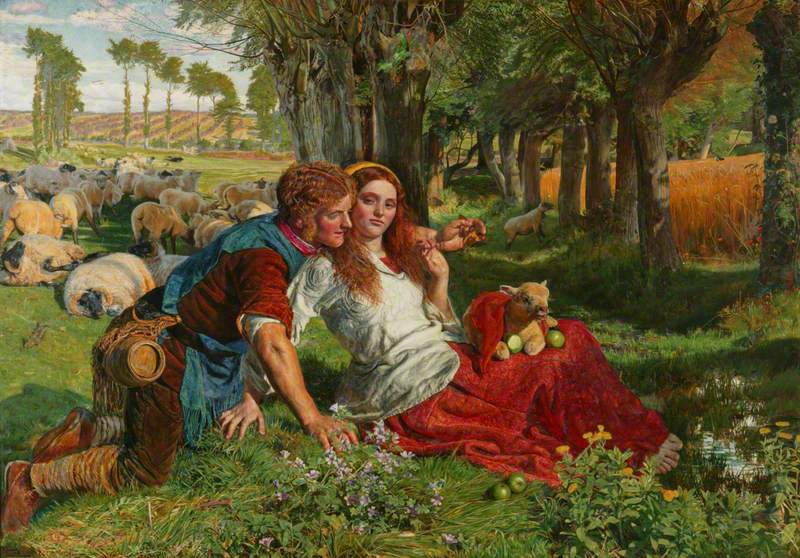

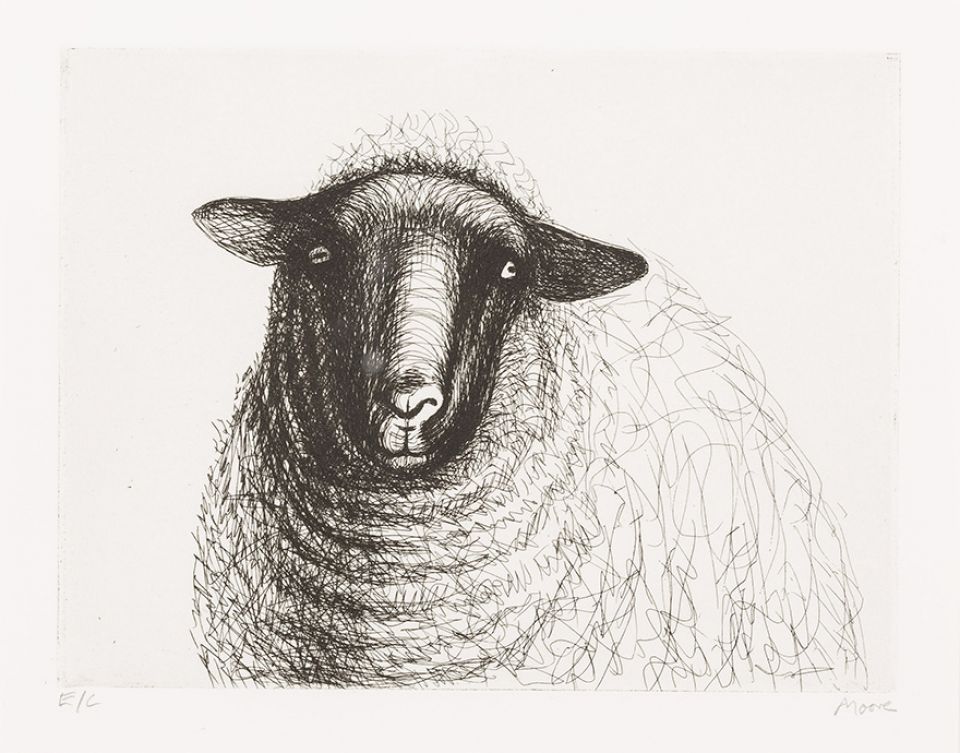

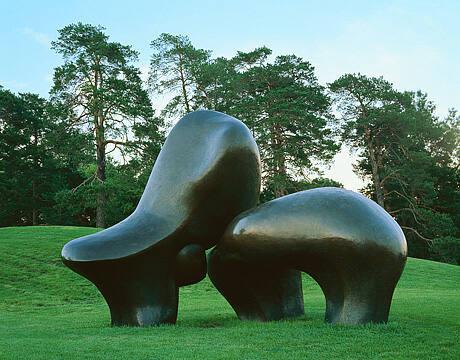

It is no surprise then that the Staffordshire potters included sheep in many of their figures – they were everywhere. And the potters were not alone. There is a history of sheep as subject, background or metaphorical symbol in many English artworks, from Thomas Gainsborough to John Constable to the pre-Raphaelites to Henry Moore (who made 234 drawings, lithographs, etchings and sculptures of sheep). Moore just liked sheep.

At first I saw them as rather shapeless balls of wool, with a head and four legs. Then I began to realise that underneath all that wool was a body, which moved in its own way, and that each sheep had its individual character.

HENRY MOORE

Even today sheep still have a significant economic impact in much of the British Isles. There are still about 35 million sheep being grazed in the UK. The domestic sheep is a multi-purpose animal with more than 200 commercially important breeds now in existence worldwide. According to the National Sheep Association, there are about 90 different breeds being grazed in the UK, but only about 15 are of major economic significance. The value of production was around £1.3 billion in 2020. With around 150,000 jobs across sheep farms and associated industries, employment in the sheep industry is worth approximately £290 million to the economy. For comparison, the United States has but 5.25 million sheep, mostly concentrated in Texas and California.

You might ask, of these many domestic breeds of sheep, which is the most popular and economically important breed worldwide? The Merino seems to be the winner. The Merino sheep is a medium-sized sheep breed and a very significant one in the sheep industry. Having been around and prized for its extremely fine wool for centuries, the Merino sheep is a founding breed for many of the modern breeds around the world today. It is highly adaptable making it easy to breed in most any climate and environment.

Sheep may not be the brightest animal according to some experts, but what they lack in sheer intelligence they make up in their sweet nature. Just looking at them gives you a big smile and the urge to give them a big hug. They are a nostalgic reminder of another time when life was simpler and a flock of sheep was the pride of the family or estate. We too enjoy our prized flock of Staffordshire sheep.

Staffordshire Figures 1780-1840, Volume 1, p.123, fig.26.62

Middle row Left: Pair recumbent white sheep – 4.2”h; 4”l. Ref. Staffordshire Figures 1780-1840, Volume 3 – p.223, fig.131.158 Centre: Pair Yorkshire Prattware sheep – 6”h; 5.5”l. Ref. Prattware 1780-1840, 2nd Edition, John and Griselda Lewis – p.78 Right: Pair recumbent black sheep – 4.2”h; 4.2”l. Ref. Staffordshire Figures 1780-1840, Volume 3 – p.224, fig.131.160

Bottom row Left: Small pleasance – 5”h; 7.4”l. Ref. Staffordshire Figures 1780-1840, Volume 1 – p.137-139

Centre: Small Prattware sheep (similar) – 4”h; 5”l. Ref. Prattware 1780-1840, 2nd Edition, John and Griselda Lewis – p.282 Right: Victorian, boy and girl in highland dress – tallest 7.8”h; 5”l. Ref. Harding Book Two – p.171, fig.2401/2402

An earlier version of this article appeared in the Spring 2022 Staffordshire Figure Association newsletter. Additional research on the history of sheep in British art by Sarah Gillett.

Win Hock collects mostly early figures, pre-1835. His wife Pat has a small collection of Staffordshire dogs and a few pastille cottages. They live in Boalsburg, Pennsylvania, US and can be contacted by email.